I try to keep things simple when it comes to pronunciation. It’s a habit that dates back to my college Intro to Philosophy course, where I learned very quickly that the hard T in Sart and the short vowel in Nietzsch-uh just felt wrong coming out of my mouth. I feel the same about French food, from maca-ron to cwah-sohn, as well as the varied ways people put extra flair on their favorite ethnic or regional cuisine. You’ll never catch me saying bolo-ngyeszeh, despite the fact that I am Italian, have a pretty good recipe, and like sounding cultured. To me, it will always be bolah-nays.

Though, somehow, my pronunciation of a particular Thai soup has been drifting recently. Just a little, the first syllable sounding like the beat of a small drum. Less like tom and more like thdum. The second syllable with just a half second of elongation, as if letting out a satisfied breath after finishing the last spoonful, khaaa.

Thdum khaa. Just say it once. You’ll feel better.

The story I was going to write was about how I traveled to the far corners of the city and ordered a bowl of tom kha from each of the seventeen Thai and Lao restaurants I was able to pull up in my Googling. Except, halfway through, something happened. I mean, what happened was some minor intestinal dysfunction from all the coconut. But after that, something happened.

The ultimate aim of this quest was supposed to be a sort of city-wide cultural survey viewed through the lens of soup. How does the tom kha in my neighborhood differ from the one at the airport? Is the one downtown, at The King and I Thai, more downtowny than the one in the far suburbs? I know, kind of a low bar as intellectual pursuits go. In retrospect, I think I just wanted to eat a lot of soup.

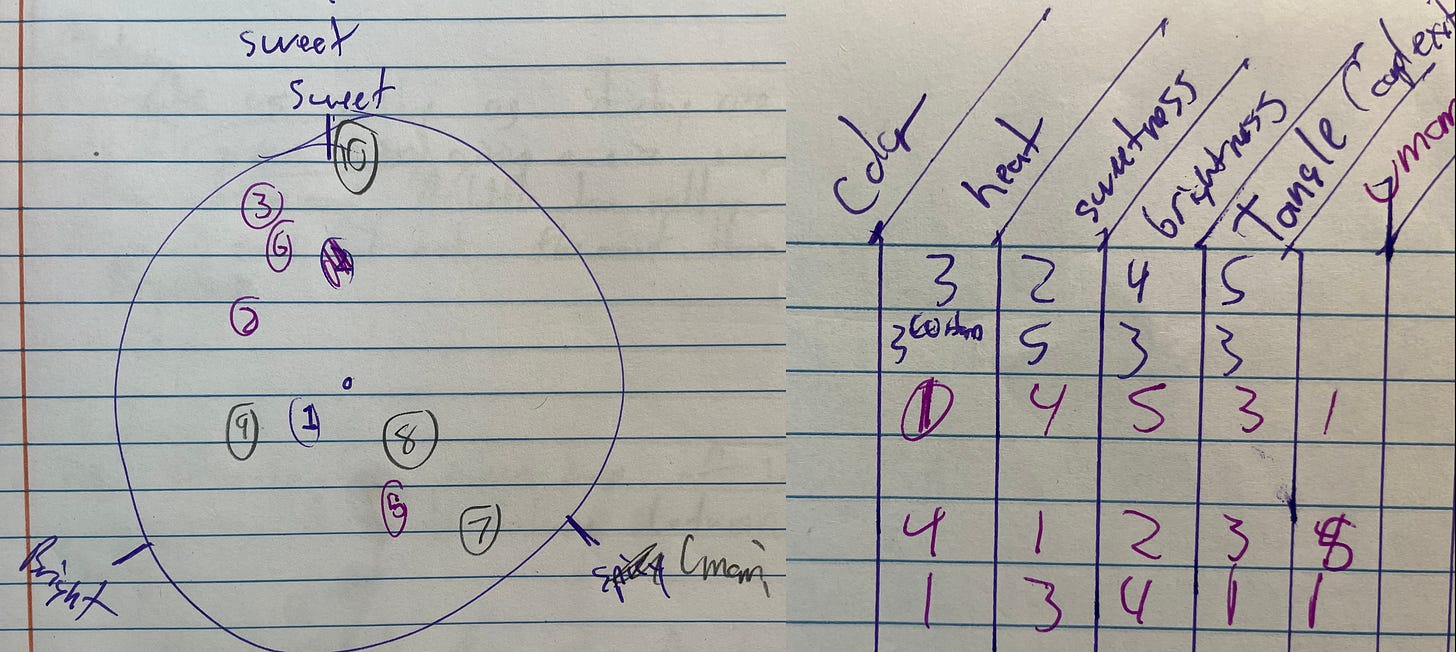

I took copious notes at each place I visited, filling pages with descriptions like “a whisper of citrus” and “a thinking man’s soup.” I drew up charts and diagrams. I truly believed that through the power of objective (or at least “objective”) inquiry, I could pin down something insightful, something tangible, for my readers.

But what I learned, halfway through my journey, is that there is nothing objective about food.

But let’s back up. I’m sure there are at least a few of you who haven’t been eating Thai carryout religiously for the past two decades. Let me explain why this dish is so important, not just to the people of the Greater Mekong Subregion, but to our collective human culture.

In the US and Europe, soup is what you eat when you’re sick, or while you’re waiting for the real food to show up, or when it’s all you have in your pantry. There are exceptions to this. I’ve had some pretty killer bowls of tomato soup or cream of mushroom in my life. I’ve labored for hours just for a taste of homemade French onion. But even in these cases, soup is not a standalone dish. At least not to me.

To understand why tom kha is different, you just need to look at its long list of ingredients. The broth alone is made of coconut milk, chicken broth, fish sauce, lemongrass, cilantro, Thai chilis, onion, garlic, lime juice, makrut lime leaves, palm sugar, mushrooms, and galangal, the more pungent cousin of ginger. To that you can add your choice of chicken, shrimp, tofu, or more mushrooms, as well as green onions, tomatoes, and bamboo shoots. It may be the most comprehensive botanical survey of a Thai jungle we have access to in North America. And after you’ve eaten it, you feel like you’ve had a meal.

And the flavor. Maybe more than any other soup, it makes a strong first impression. It tastes, of course, like a blend of its dozen-plus different ingredients. Though if you haven’t had galangal, or Kaffir lime leaves, it might be hard to imagine. If pressed, I might say it tastes like a blend of chicken soup and piña colada. Except less disgusting. But, to tell the truth, there’s no easy way to describe its flavor.

And that’s exactly why my quest stopped dead in its tracks. Because the more I tried to pin down the flavor of tom kha, the farther away I got from any sort of objective answers.

Professional chefs and experienced foodies like to pretend that the full breadth of our gustatory experience can be cataloged neatly into five basic flavors: sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami. We’ve even been taught that different parts of the tongue are dedicated to different tastes. That the tip is more sensitive to sweetness. That the back is for bitter. And that the way we know these things is, we suppose, through science.

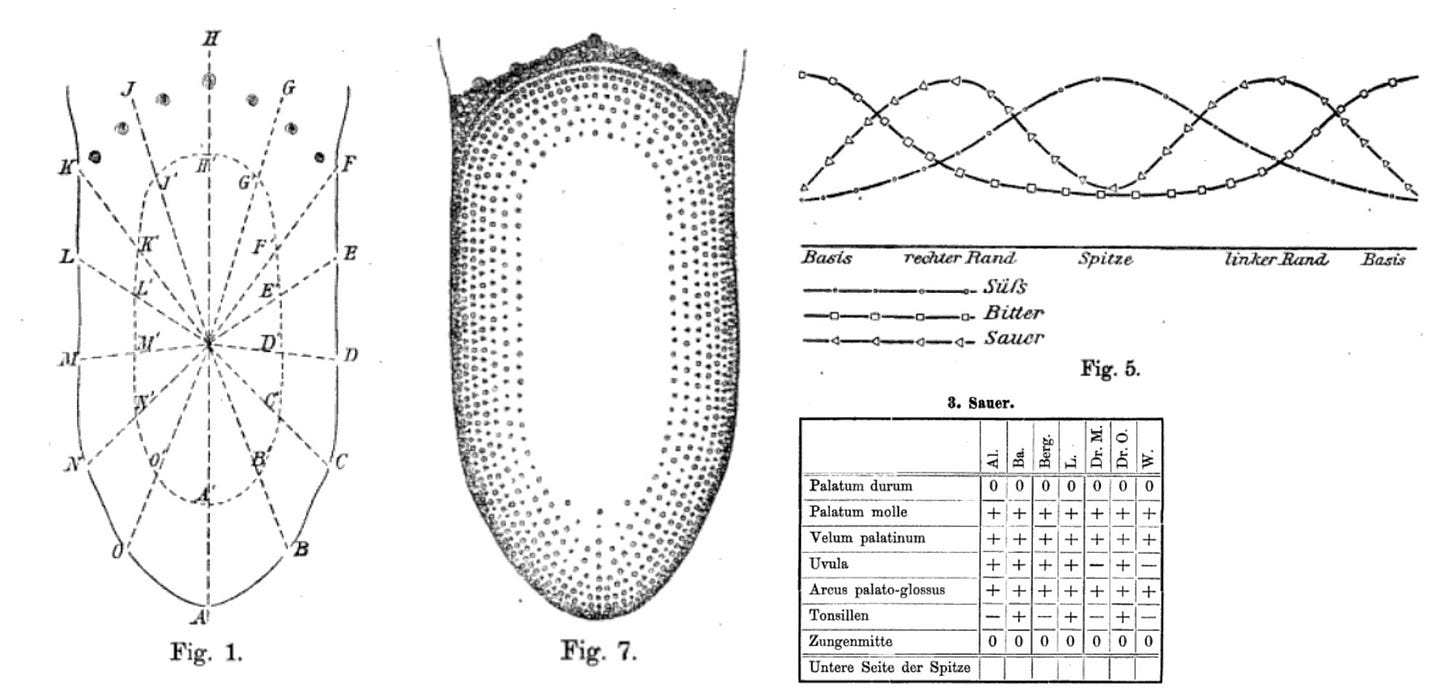

Actually, much of what we’ve been taught about taste comes from one 1901 paper, Zur Psychophysik des Geschmackssinnes which, despite all the cool diagrams, never really made any of the bold claims we attribute to it. While it does identify different regions of the tongue, and does find a variance of taste receptors in each of these regions, this variance does not add up to a difference in tasting ability that’s perceptible to us.

If you want, we could run through the paper page by page via Google Translate or even go on to trace the whole lineage of our modern notions of taste, through the thousand-year-old Chinese culinary tradition that codified several of our basic flavor words, and the 1825 publication that never stops being fun to quote--“Dessert without cheese is like a pretty woman with one eye.”

But we don’t have to. Because if we think about any of this stuff for more than two seconds, it becomes clear that it never made any sense at all.

Take horseradish for example. Using just the five basic tastes, how would you describe its flavor? It’s not sweet, salty, sour, or umami. You might be tempted to call it bitter, but is that really the word you would use to describe it to someone who hasn’t had it? Realistically, you’d probably just say it’s spicy. Then you’d pause for a moment and clarify that it’s not hot like a jalapeno, but more aromatic. Except, maybe pungent is a better word. You sort of taste it in your sinus. Get it?

The longer you talk, the clearer it becomes that our language is totally incapable of describing the flavor. This is true when trying to convey pretty much any taste. Try to describe the experience of eating a grilled cheese without using the word ‘cheesy.’ Try to find even one word that comes close to explaining the flavor of fresh-baked bread. We have plenty of texture words--crusty, flaky, chewy, soft, springy. But the taste of even the most common food is still totally outside of our linguistic capabilities.

If it wasn’t clear by now, this is a pretty frustrating problem for me, the guy trying to write the article. But actually, it’s not a problem I haven’t wrestled with before. I worked for several years as a food writer, mostly churning out blog posts with titles like Top Ten Substitutes for Mayonnaise or Are Twizzlers Vegan? It was a dark period in my professional life, though it reliably gave me plenty of intellectual puzzles to chew on, like putting to words the subtle difference in flavor between an almond and a cashew. Or explaining what Dr. Pepper tastes like. Or answering, once and for all, how much does a potato weigh? These are all, by the way, real examples of assignments I was given.

But actually, now that I’m not doing it for a living, it’s easier to appreciate this weird relationship between words and food. Because think about it--today, there’s no painting, sculpture, song, film, or novel that can’t be digitized and sent to the other side of the planet in two seconds. While it’s true that seeing a photograph of a work of art isn’t quite the same as seeing it in person, it’s better than the alternative.

Imagine you’re alive in 1652 and eager to see the new work of hot-shot sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini that just dropped. You have two options. You can either go to the Santa Maria della Vittoria yourself or ask your buddy who works there to describe it to you.

The problem is that your friend is kind of a philistine. “It’s just some kid holding an arrow,” he keeps saying.

With food, it’s still 1652, and we’re all just as inarticulate as our Philistine friend. Sure, we can take pictures. And we love to. Obsessively. But what does a photograph of a cheeseburger really do to bridge the gap between the person who ate it and the person sitting at home with just the one remaining Lean Cuisine haunting their freezer? It mostly just reminds you that you wish you had a cheeseburger. That’s what makes food different from other art forms. Because honestly, is there any sculpture in the world that satisfies you as well as a burger?

And so, in my failure to adequately describe the taste of tom kha, I’m turning my attention to the bigger question. Which is--well, I guess I don’t know what it is yet. But I know it has something to do with ephemerality. And satisfaction. And how the things that are most short-lived are also usually the best. For the rest of the month, I won’t be looking at the paintings and sculptures filling our museums, or the books on our shelves, but turning instead to the experiences that live in our hearts.

Actually, probably not the experiences that live in our hearts either. Maybe I should start, like, outside? It’s June after all, and we only have a few short months to enjoy all summer has to offer.

Hey, thanks for reading! Anyone who regularly makes it to the bottom of my newsletters is okay in my book. Better than okay. Great. But you know what would be a huge help? Sharing. Grape Eater still has just a small following, and I definitely notice every time I get a new subscriber. Actually, I yell across the apartment to my wife, “I got another one!!” each and every time. So if you think your own social media following might like this, post it on your page!

"This is fantastic work" is vague. Your piece deserves more. Stay tuned for more reflections from one who started out trying to write restaurant reviews (because the "mainstream press" versions around here are so lamentable) and realised early on that they are really not worth writing if one has as a priority to talk about the grub of the restaurant under consideration. It soon dawned on me that a worthwhile restaurant reviews talk about many things other than food. In fact, the less that food is mentioned...the better is the review.

This is fantastic work.