Isabel Kent

Quitting the Monastery

Think of Sukiya as the Japanese Denny’s. Actual Denny’s is also in Japan, but it’s considered special occasion food, featuring Amerikan classics like Rice Casserole With Hamburger Steak and Curry Sauce. Sukiya, however, doesn’t make any special effort to impress. They know anyone stumbling through their door at three in the morning is desperate. Like Brad, still jet lagged, sitting down at a linoleum table and pointing haphazardly at the menu.

“Ah! Saba choushoku desu,” says the server, with a casual bow. He leaves before Brad needs to use either of his Japanese words, off to get the saba choushoku ready.

It was only later, now actually, while writing this, that Brad thought to look up the translation. Mackerel breakfast, as it turns out. Maybe not the most frightening thing you could order in Japan, but keep in mind that Sukiya is not known for the quality of its seafood. It would be like ordering the mackerel at--well, at a Denny’s. Luckily, Brad is blessed with a tendency to masochism, and so he takes these things in stride. It’s exactly the kind of thinking that landed him at a 24-hour Japanese diner in the first place.

The server is back in five minutes, setting down a shocking number of bowls on a plastic tray. The unhappy sliver of fish, along with miso soup, various mystery pickles, an individually wrapped square of seaweed, chewy but flavorful roast beef, a styrofoam casket of fermented beans, and a single egg still in its shell.

Before sunrise is the perfect time to eat too fast. Brad isn’t even starving but somehow manages to juggle multiple bowls at once, shoveling rice, drinking miso straight from the bowl, chop-sticking the whole piece of fish and biting it in half. The fermented beans, somehow both slimy and sticky, are the only thing categorically disgusting. He chews them for a full minute before deciding that swallowing is probably the best option.

Most of it is good, some even delicious, though nothing that an American stomach registers as breakfast. The egg he’d only saved to keep him company, a familiar face in a crowd of strangers. He cracks it against the side of the table and watches its sadly unhardboiled innards ooze straight into his lap.

People live all kinds of different ways. That’s not the moral of the story, but it is true. While it’s as evident as egg dripping down your pant leg, it’s still a hard concept to fully wrap your head around. Consider, there are people in the world, lots of them, who see an egg in a bowl and think, “That better be fully liquid or I’m asking for my 400 yen back.” And then do whatever it is they do with a raw egg in Japan.

There are also people in the world like Isabel, who, exactly 294 days before the Osaka Egg Incident, still hadn’t had breakfast. She’d been sitting the past three hours, her legs arranged in different painful configurations, trying hard not to think about food. In other seasons, she’d hear crickets or sycamore pods falling onto the roof, but in winter the zendo is especially quiet. The sun has not yet started slanting in to warm the floorboards or light the day. Just a single cranky jay outside, maybe the last to find a morning worm.

Eventually, meditation is over. Then a half hour of Morning Service, ending with a final bow. Now it’s time. She takes a second to adjust her robes before starting okryoki.

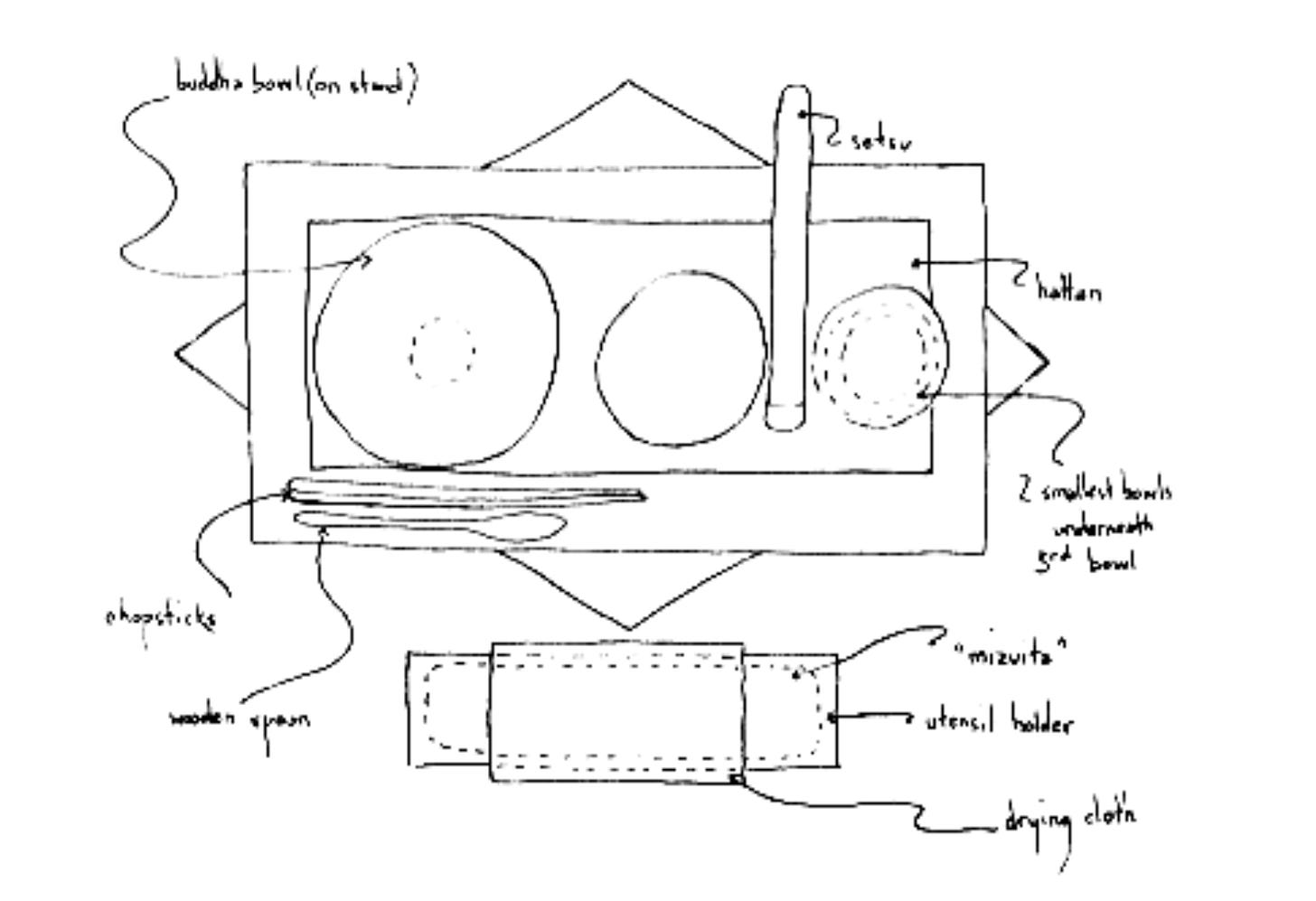

The bowls are waiting behind her. There is no special instruction for how to turn and grab them, other than to do so with the full weight of her attention. However, after this point, there are hundreds of individual movements to remember. Each comes with its own little spark of satisfaction, and her brain glows faintly as she sees the tied corners of her okesa, the wrapping cloth, pointing to the right, as they should be.

The details are, of course, everything. She plants the first three fingers of her left hand on the knot, pulls at the corner, and opens the okesa, smoothing its left and right triangles. Inside, the chakin, a small drying cloth, waits on top. She picks it up with two hands, pinches the center on either side, and flips the end toward herself, folding it in half. She folds it again to make a square, with hems in her left hand and creases in her right. Then folds it again into thirds. She pinches the top left and bottom right corner, flips it over, and sets it on the kinchaku. She picks up both together, turns 90 degrees clockwise, and places them between her knees before her.

There was once a time when she had to think about these individual steps. Now they just blur together into a single, fluid motion--Takekin, okesa, jihatsu, shiruwan, chawan, setsu, spoon, and chopsticks, all know where to go on their own. Isaben’s hands seem to know too, as though they belong to someone else. The whole time, her voice chants without stopping, someone else’s words, someone else’s rhythm.

With everyone’s bowls and utensils arranged, the servers come out with the food. Isabel was expecting rice porridge, though it smells more like some vegetable. The servers kneel before the hungry monks, filling bowls according to hand gestures. A rising upturned palm means stop. A pinching thumb and forefinger means just a little, please.

In Zen, perfection is the goal but snags are always expected. It took months before any of this felt natural. Isabel made mistakes all the time, constantly chiding herself, always embarrassed. And so it didn’t take much effort at all to empathize with the server who’s just dropped a lump of tofu near his foot. The sting of panic, wash of shame, residual prickle that lingers after--all so deadly serious when it’s happening to you. Maybe that was why she couldn’t stop laughing.

It might be hard to understand, if you haven’t spent the last six months observing silence for 18 hours a day. If you don’t know what it’s like to dedicate your life to ritualized privation, you certainly have not experienced a case of the giggles quite as bad as this. Because to Isabel, and the monk sitting beside her, this was the funniest thing that’s happened in the history of the Earth. The poor guy, frantically hunting around the zendo for the offending curd, looking like a nervous duck as he bobbed his head around bowls and cushions. The elders’ wooden faces, mysteriously untempted by the joke. And Isabel, laughing, the embarrassment now hers to share in, as disapproving glances drift over. More and more of them are converted, red, wet faces radiating out like ripples in a pond.

Maybe you had to be there.

Once the food is served, there’s six minutes to eat, the only rule being silence. When done, they lick their utensils clean and fold everything back into the same neat parcel. Isabel ties the knot on top, packing up her guilty laughter with the bowls.

If you’re still having a hard time finding the humor, understand, this wasn’t just one day of Isabel’s life. It was every day, for fourteen months. The dropped tofu wasn’t the funniest thing that happened that day, but that year. After five minutes it was over, then off to an hour of studying scripture, an hour of cleaning, three more hours of meditation. When she unpacks her bowls for the next meal, the next 500 meals, nothing remotely funny happens.

Eventually, spring does come, then summer, and she’s packing to leave Tassajara for good. She saw it through to the end, after many more cold nights, hungry hours, legs pains, and unasked questions. The next fall and winter come and go and she feels like she’s still transitioning back to her old life. Even still, after another spring, another summer, and another fall.

It’s winter again, 2024, and maybe there is some satisfaction from knowing that she saw things through to the end. But talking to Isabel, for months now, I get the feeling that she wishes she could have quit the monastery sooner. She says, even now, she still doesn’t feel quite like herself.

She still meditates. Not as religiously as she did at the monastery, but it seems to help anyway. She tells me, “I recognize that there’s something happening when I sit in meditation. This is a more recent thing, since I moved out here. Just feeling like I’m settling and connecting to someplace in myself that feels very--the word immovable comes to mind. Very steady.”