On Milwaukee Kitchen - Marcie Hoffman

Framing Devices, Feedback Loops, and the Standardized Patient

It’s hard to translate a conversation to someone who wasn’t there. You’re constantly backtracking, explaining jokes, filling in crucial details. It’s the reason why we often just settle for you had to be there. It must be a fundamental law of the universe that the better a conversation is, the harder it is to put to paper. Because talking, real talking, isn’t so much about what’s being said. It’s about rhythm, mostly, a back-and-forth feeling, and the effort on both sides to keep it in balance. Kind of like playing catch, except when the ball comes back it’s a hockey puck, then a tulip, then a chainsaw. If that, uh, makes sense.

By that analogy, I think writing is like juggling. And acting is like--well. I’m not an actor. You’d have to ask Marcie what it’s like.

For more than 20 years, she worked with the experimental theater company, Theater X. I wish I could convey how impressive this is to me. It’s like finding out your cousin was roommates with Serena Williams, and had once given her tips on her backhand. Theater X traveled the world. Amsterdam, Great Britain, Japan, showing up in various journals across Europe. Now defunct, it’s been canonized as one of those names Milwaukeeans love to mention, alongside the Violent Femmes and Golda Meir.

Though to Marcie, the connection is more personal. “This kind of work is like falling in love without the disappointment,” she says. We had a chance to talk recently, at Paul’s house. It was supposed to rain that day, so when I made it through the door before it started, I was already feeling good. Marcie and Paul were chatting in the kitchen when I got there. Aside from being collaborators, they’re friends.

Though actually, if you’re an observant Milwaukee Kitchen fan, you’ll notice it’s not Paul’s home pictured above, but the set of his YouTube cooking show. The difference is subtle. You have to look closely. They have identical stoves and countertops. The walls are painted the exact same shade of light green. You’ll find Penita both places, though she didn’t reply when I spoke to her.

Either way, Marcie seemed perfectly at home there. Paul too, though I could tell he was feeling smug for having gained the upper hand in our ongoing battle for contextual supremacy.

Let me explain. He never told me so directly, but I get the feeling Paul dislikes attention. He tolerates it as a necessary part of being a successful artist, but like many artists, he’s happier to spend days on end in quiet privacy, working. This privacy is the other necessary part, not for all artists and writers, but many. So when he invited me into his home to do my next three interviews, I knew something was up.

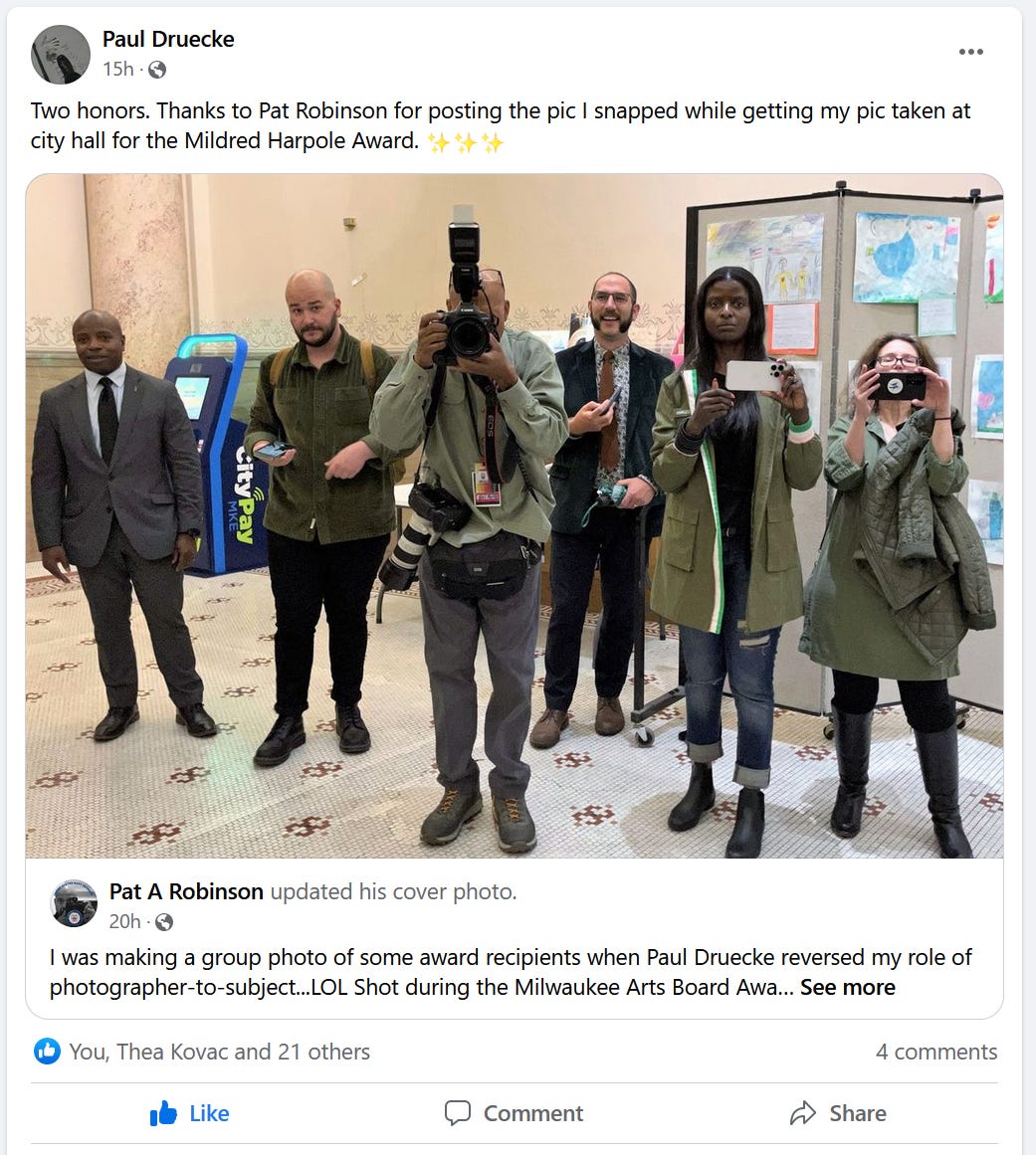

If you don’t believe me, look at this. Just one example of what the man is capable of, when forced to endure public scrutiny:

So you can understand why I only accepted his invitation with the greatest caution. Clearly, it was an effort to outflank me. He saw me framing his experimental cooking show, and decided to build an even bigger frame and fence me in. It was a real tete-a-tete. A game of cat and mouse, if you will. I checked his shelves for hidden cameras, nearly tore down the curtains, if only out of spite. I took note of the mathematical precision with which the stools had been arranged around the kitchen island.

In reality, it was a lovely time. He made a pitcher of mint tea, and was thoughtful enough to be out running errands while Marcie and I talked. In my experience with Paul, he’s never anything less than perfectly nice. Marcie and I both took him up on the tea, though we talked over the kitchen table rather than the island.

Where my conversation with Anika started off scattered and only gradually found its focus, talking with Marcie was just the opposite. We started with the big ideas. What Makes a Credible Performance? What Differentiates the Arts and the Sciences? What Commonalities do Writing and Acting Share? I like heady talk in moderation. It’s fun, like going to a costume party. Today I’ll be the guy who stoutly insists that an artist’s craft must be driven by curiosity, and a scientist’s by reason. Tomorrow, maybe I’ll take the opposite stance.

It was fun while it lasted, but what I wanted most was to get to know the real Marcie.

The real Marcie, I found, or imagine I found, is a peerless conversationalist. Always gracious and not stingy with compliments, it’s impossible not to like her. At the same time, she has a definite edge, a sense of humor that cuts both ways. With these and other talents, she can steer a conversation wherever she likes. It can be a little daunting for an interviewer or, I bet, a director.

My favorite Marcie scene on Milwaukee Kitchen comes early in episode 17. The premise is that Paul’s kitchen disposal is on the fritz, but he’s making the best of it. It’s a more fraught atmosphere than most episodes, and the tension is palpable from the start. Paul, after explaining the situation to Marcie, hopefully suggests she might chop onions. Though Marcie, being well-versed in the art of improvisation, does not limit herself to yes-and. She says, simply, “no,” without even a hint of a smile. Paul persists, the solitary, unchopped aromatic waiting in the foreground on its cutting board. It’s only after much effort on his part that Marcie concedes to even acknowledge the vegetable.

I’ve always found obstinate people easier to talk to. I guess knowing the other person’s preferences makes it easier to learn who they are. Obstinance isn’t always Marcie’s most obvious personality trait, though I think it is her authentic self showing through on camera.

After her Theater X days, she found no lack of opportunity to translate her acting skills off stage. She worked as a Docent Tour Coordinator at the Milwaukee Art Museum for two decades, and now at Olson House, where she sells Scandinavian design pieces and locally-made art.

Alongside her other roles, Marcie works as a standardized patient. It’s one of those jobs you don’t consider and then realize it’s the backbone of an entire industry. The job description is simple on the surface. You’re taken to an examining room in a hospital gown and sat on wax paper until the doctor comes in. It’s actually a student doctor playing the role of a real one, as Marcie plays the role of the patient. She’s assigned a medical condition, anything from a cold, to high blood pressure, to pneumonia, substance abuse, or a terminal illness. The idea is for the doctor to make an accurate diagnosis, based on the symptoms she portrays.

The challenge of this should be easy to appreciate if you’ve ever faked an illness to get out of school. If you haven’t, try it for yourself now. Pick a medical condition at random and see if you can convince your friends and family you’re not faking. I got Meniere’s Disease.

Marcie says playing the role of a sick patient is only half the work, that the real meat is what comes after. It has to do with what doctors refer to as clinical communication skills, but what we usually call bedside manner. It’s a broad field on its own, but the idea is that doctors can better care for their patients if they have a strong rapport. There’s an “unbelievable spectrum,” Marcie says, of skill in this area, which in my experience with doctors sounds about right.

Because, needless to say, not all patients come to their doctor with sprains or sniffles. Communication isn’t always straightforward. Imagine, as Marcie did for one particular role, that a 17-year-old woman has been in a car accident. During the course of her examination, the doctor discovers she’s also pregnant. By law, doctors are sworn to confidentiality, meaning that the worried mother wringing her hands at her daughter’s bedside needs to be led out of the room before the pregnancy can be discussed. Once she is, the doctor is faced with the task of informing a wounded teenager she’s having a baby.

A rough day, to say the least, for all involved. But during a clinical skills assessment like this, the work isn’t done. After the examination and the bedside mannering, both the student doctor and standardized patient sit down again, for round two. This time, Marcie’s no longer a patient. Now she’s taking the lead, giving feedback on their examination and communication skills, breaking down every aspect of the experience. Basically, she’s giving them feedback on their feedback, employing her own bedside manner as she tries to diagnose whatever social or emotional maladies may or may not be afflicting their ability to connect.

Diseases, injuries, and other medical conditions a doctor faces each day are always, without exception, attached to a human being. Yes, it’s necessary to have an encyclopedic knowledge of anatomy, biochemistry, pathology, and pharmacology, but also, physicians need a well-traveled and thoroughly-annotated map of the human condition. Marcie is their expert tour guide, making sure they don’t miss any important landmarks.

What I like about this exchange is the reciprocity. She and this twenty-something-year-old future-doctor are passing feedback back and forth. After Marcie’s given feedback on their bedside manner, her feedback is fed back, just like any working person, at a performance review. She takes note, tweaks her approach, and feeds back into the system. I’m definitely romanticizing. It’s her job, after all. But if we have to have jobs, we can at least hope for reciprocity.

I’d say, by now, Marcie and I have a pretty good feedback loop going. During the course of the writing process for this piece, I let her look over my draft, and even made a few edits based on her feedback. It seems only fair, given all the attention I’m pushing on her. And honestly, it’s more fun to work that way, passing the ball back and forth.

Of course, Paul’s part of the loop too, as we continue to out-frame each other. Actually though, I didn’t have that quite right. Thinking about it again, I wonder if Paul’s not building a frame around me after all. Not just me, anyway. Maybe the frame is around us, all of us, himself included. The intention being, I guess, to make a shared space.

Can I say for the record that I’m getting sick of these sentimental endings I keep sticking myself with. If you hate them too, please feel free to write in something less maudlin (it won’t be hard) in the comments below.

Also, please subscribe :)

On Milwaukee Kitchen is a five-part series where I speak to the cast of a locally-produced made-for-YouTube cooking program. If you haven't checked out the show for yourself, I would recommend looking at their most recent episode, Sweet Sourdough.