The Milwaukee Institute of Regular People Just Trying Their Best, Okay?

Adulting, Dauntability, and Dropping Out

Can I apologize for the word adulting? It existed years before my own adulthood but I definitely contributed to the generational spirit that spawned it. It’s a typically Millennial mindset, the belief that the unremarkable is worth remarking on. That we’re being clever or virtuous by drawing attention to what everyone has known all along. Like the fact that exercising and going grocery shopping in the same afternoon is a pain. That this pain is, for some reason, remarkable. It’s our equivalent of airline food jokes. We keep repeating the same observations even when they stop being funny. Maybe we find the familiarity comforting.

Of course, Millennials came to the same conclusion as Jerry Seinfeld and every other human being before him. That adulting is just another phase. Isn’t it a weird feeling, noticing yourself moving from adulting to plain old adulthood? Now, even the unremarkableness is unremarkable. It’s just us, sitting in a chair, pressing each key in the right order to spell Let’s circle back next week, Carol. What ever happened to us?

I guess I’m in kind of a mood. Do you mind if I ask a philosophical question? You do mind? Well, here’s one anyway.

What’s the best-case scenario of your life? Or, to narrow the question a bit, what’s the best-case scenario of your career? What would your existence look like if everything had gone your way, every standardized test, college application, job interview, meeting, proposal, performance review, studio visit, grant application--everything? What if you got everything you ever hoped for? Or more than you could hope for? What if you reached the highest success you can imagine?

What would that even look like? If you’re an artist, it might mean wealth. Or popularity. Or better yet, esteem. Maybe you like to imagine PhD students writing hundreds of pages on the few lines of charcoal you scribbled one afternoon, a decade ago.

Or maybe it’s about legacy. Do you fantasize about generations carrying your name through the ages, outliving any memory of Van Gogh, Pikachu, or 7-Up? Is it alluring, the idea of our children’s, children’s, children’s, children, using your paintings to make memes and merch?

That’s the funny thing about best-case scenarios. And yes, by funny, I mean sad.

Luckily, you and I have a zero percent chance of ever having to worry about it. Maybe not technically zero. The actual number can be expressed by a simple arithmetic function. That is, the number of artists who have ever lived, divided by the number of artists the average person can name from memory. So, roughly, a billion divided by six.

But artistic legacy isn’t everything, right? Most artists I know would be happy with a medium-nice house in Shorewood and enough left over to ditch their bus pass forever. How likely is that, exactly? Maybe one out of fifty artists? One out of five hundred? Incidentally, do you enjoy long and frustratingly imprecise footnotes?1

Whether you read the footnote or not (don’t read the footnote) the reality is that for ninety-nine (point nine nine nine nine) percent of studio artists who have ever lived, in any place or time, art is not a career. It’s a vocation, a calling, that may afford you a surprisingly sturdy sense of purpose, but never a house or car.

This may be a good juncture to remind myself that this, part 3, is supposed to be the uplifting part. I haven’t been trending in that direction so far, so let’s take a second to acknowledge, without irony, that it’s actually kind of cool, the fact that we still have artists despite the daunting material reality.

Don’t you think? And it’s not just a few roughnecks living out of abandoned warehouses either. It’s a whole class of people, a whole sphere of activity, that’s been somehow pried loose from capitalism. We tend to overlook this. I think because artists and progressives prefer to imagine themselves as a rebellious minority, we don’t fully appreciate the fact that artists are everywhere. There’s a temptation for capital-A art-world Artists to cast woodworkers, crochet enthusiasts, and Sunday painters as mere hobbyists. But in a world where only the smallest fraction of us are making a living off our work, maybe we can’t afford to be such strict gatekeepers.

Of course, many of us still wish we were somewhat less liberated from capitalism. But in the spirit of uplift, let’s acknowledge the fact that even when artists fail to make money, they continue, dauntlessly, making drawing after drawing, after paperclip mobile, after digital media installation. It doesn’t matter that the work has nowhere to go but our closet shelves and desktop folders. Where the work goes isn’t the point.

That’s how I feel about Saturn, anyway, the part about dauntlessness. Though I don’t think they’d be satisfied keeping their work closeted. Saturn grew up in a small town in Texas, with loving and hardworking parents who did just about everything they could to keep their child from pursuing art as a career. For four years at a STEM-focused high school, Saturn squeezed precious few drops of artistic gratification from the rigid orthographic drawings they were assigned. (The kind of thing you’d see on a design patent or blueprint.) It might have discouraged a less determined person, but to Saturn, it lent a sense of focus. Little by little, art became less a hobby and more an identity.

Their current work looks to me like a celebration of having escaped orthographic drawing forever. I think dauntless is again a good description. While Hannah may have been the most professionally-oriented student I talked to, Saturn is doubtlessly the most driven. They make art at breakneck pace, constantly working and meeting new people. They make friends wherever they go, growing their circle little by little.

Ultimately, they’d like to be an art director in film or television. Maybe they’ll reach this goal, or maybe they’ll find something that suits them better. What I’m sure of is that Saturn will keep going, in some fashion, as an artist. Career is beside the point. Saturn makes art because they have to.

Which is not true of everyone who goes to art school. In fact, I would say young artists tend to take their pick from a buffet of identity crises. It comes with the territory and certainly doesn’t disqualify you from making art. For quieter personalities, it could even be an asset.

Going just on the volume of her personality, I would say Pili is unlike Saturn. She’s reticent. Analytical. She’ll blink a few times before responding to your question. I can imagine her, in ten years, being an intimidating presence to anyone trying to win her respect. I don’t mean to pigeonhole her. I can also imagine Pili being a fun person to throw rocks into a river with. People are complicated.

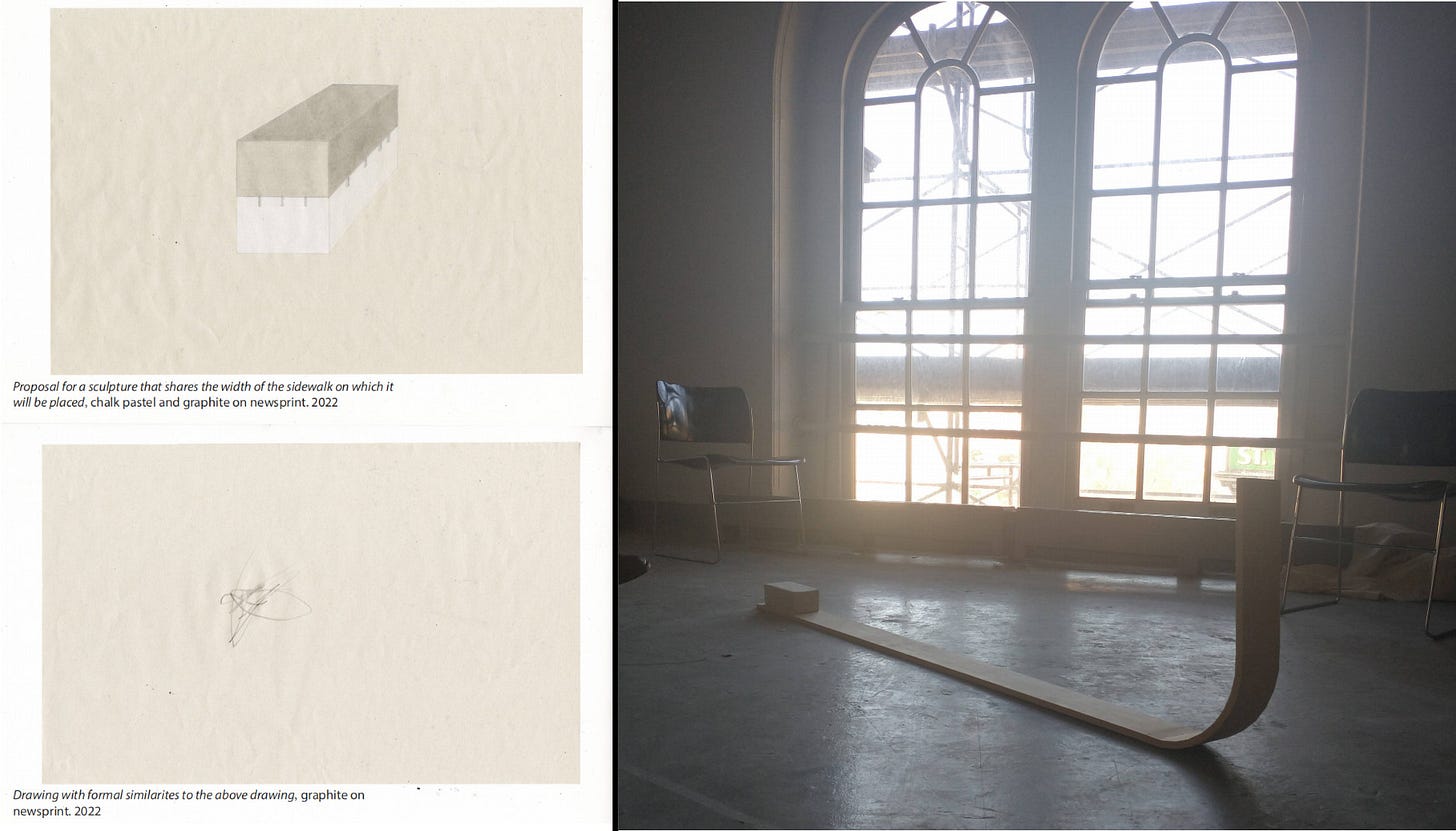

And they’re all different. While Saturn wants to escape orthographic drawing, Pili reinvents it. Her work, like her personality, is quiet and analytical. Though if you’re paying attention, it’s also pretty funny, visually punning on high modernist conceptual art. You might call her work cerebral. You might also call it goofy as hell. It is, after all, a piece of wood with a brick on it. I may have once enjoyed a similar phase.

Pili, I would say, is a dauntable person. Talking to her, I got the sense that she’s a little daunted. While identity crises don’t disqualify you from being an artist, it’s worth remembering that not everyone recovers from them. Not everybody needs to.

In our conversation, it became clear that Pili isn’t as sold on the whole artist thing as she used to be. The novelty has worn off, and she’s been thinking more and more about switching out of her school’s art program. I didn’t know Pili well, so it was hard for me to gauge whether this was a temporary lapse in confidence or something she’d thought through. I asked what led to the change of heart and what she told me was “the dynamics of the art world are foreign” to her. That she’s, “cautious of anything having to do with private acquisition.” Which, you know, sounds like the kind of thing an intellectually agile person says when they don’t want to answer your question.

I got off our call and jotted down some notes. I stared out the window and ate a few handfuls of Cheez-Its. A month passed and it was still bothering me, so I asked again.

As of now, Pili is preparing to apply to law school. She says she doesn’t regret her time studying art, but that it was a chance to learn more about herself before moving on. She says that she doesn’t see any meaningful difference between lawyers and artists, or herself and artists, that the only difference is how one structures their life. She also said

Which pretty much sums it up.

I think the mistake a lot of artists make, young and old ones both, is believing that art is primarily a field of study, or a job, or worst of all, a career. You can study art, even make money off it, that’s true, but be careful not to forget that art is as broad and deep as religion. Not a religion, but all of them, together. Art is a self-determined system of belief and practice. It’s a way of understanding the world, but also a way of living in it. If you do figure out a way to make it profitable too, fine, go for it. But don’t be mad if you’re regarded as a huckster. Career artists, no matter how much or little talent they have, are simply people who have learned to make money off what human beings have been happily doing for free, for thirty-thousand years. It’s nothing to be ashamed of, but nothing to envy either.

Making art is our resting state. It’s the most natural mode of existence we know. If you don’t believe me, look in any retirement home, or daycare, or prison, or anywhere else you can find groups of people who aren’t distracted by a day job. You won’t find many artists there, just lots of ordinary people making art.

And that’s about as uplifting as I’m able to be.

So what are art schools, ultimately, but places to receive training in a craft we all know by nature? What are art galleries but institutions dispensing validation to people who, if they only knew, have no use for it? I wouldn’t characterize either as particularly vicious. Maybe just ridiculous. They’re the most successful hucksters of culture who, like a Dickensian tax collector, “we make necessary by our faults and follies, or by our want of worldly knowledge, or by our misfortunes.” Ridicule, but don’t blame.

And, given all that, what exactly is our responsibility here? That was the point, wasn’t it, to make writing that does something other than criticize? As people with slightly more perspective than they had before starting, shouldn’t we put our insight to use? Well, how?

It depends on who you are. If you’re an artist, maybe it means wondering whether you actually do care to continue participating in a system of validation that doesn’t serve you, or if there are places other than a gallery to show your work. If you’re a professor, maybe question who, specifically, your curriculum is serving. If you’re an engineer or a lawyer, remember to honor your extracurriculars. If you’re an arts writer, consider paying less attention to galleries, museums, and moneymaking people, and more to the vast swath of culture that lies outside the system.

Thanks for reading! I think it’s pretty obvious that this is a personal topic for me, so I hope this series wasn’t overburdened by my feelings. Next time, and for a long while after, I’ll be enjoying my more friendly and comfortable mode, just talking to artists and telling you what they say. And yes, by artist, what I mean is, literally anyone.

Actually, I spent an insane amount of time researching this question and didn’t come up with any satisfying numbers. You’d be surprised how hard it is to estimate the total number of artists there are vs the number of opportunities available to them. The NEA says 2.5 million artists in the US. Except, unsurprisingly, this government agency’s definition of an artist is bizarrely out of touch with any useful reality. So, I looked at their stats on the number of degrees in studio art awarded, which totals roughly to 600,000 since 1987. But then again, the vast majority of working artists didn’t even go to art school. Both figures feel about as relevant as simply totaling the number of Instagram accounts, which happens to be 2.35 billion. It sounds absurd, but then again, what Instagram user wouldn’t take the chance to show their photos in a gallery, if given the chance? We might say, very (very) roughly, that there are more than a million artists in the United States currently. Probably quite a lot more.

And so how many exhibitions are there? Well, there are about 1,400 galleries in New York City (which accounts for about 90% of the country’s total art revenue). If we are generous and estimate that each of these is able to represent seven artists, then we have about 10,000 slots available. That’s one out of a hundred artists who have the chance to regularly show their work. Though, of course, showing art isn’t the same as selling it. How many paintings are sold for each one shown? One out of ten? One out of a hundred? I have no clue. But if your goal is to make a living, you need to find a way to sell them regularly, at least a few each year.

I don’t offer these numbers and estimates with the expectation that they’ll be useful in practical application. Rather, I want to take stock of the figures that are available to us, few as they are, and sketch some picture of the reality that every artist already knows, and has long since compressed into a compact ball and buried somewhere near their stomach-to-butt region.